✆ + 1-646-235-9076 ⏱ Mon - Fri: 24h/day

AI, Privacy, and the Smart Home Paradox: How Much Should Devices Really Know?

The concept of a “smart home” has long ceased to be a futuristic dream and has become an everyday reality. Today, this term refers to a comprehensive ecosystem of devices connected to a network and capable of interacting with each other, automating household processes and making users’ lives more comfortable. Smart speakers, intelligent thermostats, lighting systems, surveillance cameras, home appliances with Wi-Fi or Bluetooth — all these elements form the foundation of the modern connected home.

Artificial intelligence plays an increasingly important role in this ecosystem. It is AI that allows devices not only to execute commands but also to understand context and even anticipate human needs. For example, a smart thermostat can learn to optimize heating system operation based on residents’ schedules; a voice assistant can remind about an important meeting by syncing with the calendar; and a security system can automatically detect suspicious activity. Thanks to machine learning and data analysis, the smart home is gradually acquiring the ability to make decisions autonomously.

However, as intelligent capabilities grow, so does the central question: how safe is it to allow technology to know so much about us? This is where the paradox of the smart home emerges. The more information devices collect, the more efficiently they can operate. They adapt more quickly to user habits, provide a high level of personalization, and help save time and resources. Yet at the same time, this very data becomes a potential threat to privacy.

To be truly “smart,” the system must have access to intimate details of daily life: when residents leave and return home, what programs they watch, when they go to bed, what products they order, and even how they feel physically. If this information falls into the hands of third-party companies or malicious actors, it can be misused — ranging from intrusive advertising to identity theft or even direct threats to personal safety.

Smart Home and the Role of AI

One of the most common examples of using AI in a smart home is voice assistants such as Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant, or Apple Siri. They don’t just perform basic tasks like playing music or setting a timer; they become a central hub for managing the entire home ecosystem. A voice assistant can turn on the lights, adjust the temperature, order groceries, or sync the user’s calendar with household activities.

Another area is smart cameras and motion sensors. Unlike traditional video surveillance systems, these devices are integrated with AI, enabling them to recognize faces, distinguish a person from a pet or from the accidental movement of tree branches in the wind. This significantly reduces the number of false alarms and increases security levels. Additionally, algorithms can analyze behavior patterns — for instance, if a child comes home from school, the system can automatically notify the parents.

In the field of energy management, AI helps save resources significantly. Smart thermostats can learn the residents’ daily routines and optimize energy consumption: lowering the temperature when no one is at home or warming up the rooms in advance before the owners return. Lighting systems can automatically adjust brightness and color temperature depending on the time of day or the level of natural light. Thus, artificial intelligence in the smart home becomes not only a tool for convenience but also for efficient resource management.

A key function of AI in the system is need prediction. Instead of waiting for a command, the system tries to anticipate what the user requires. If you usually wake up at 7 a.m., the system can open the curtains, start the coffee machine, and provide updated weather or traffic information. This level of personalization creates the illusion of an invisible assistant that always acts at the right time and in the right way.

Where the Line Lies Between Comfort and Invasion of Privacy

Since a smart home is an environment where numerous devices constantly collect data, creating a detailed picture of a user’s life, it becomes possible to make everyday living as comfortable as possible: lights turn on when you enter a room; the air conditioner adapts to your habits; the fridge notifies you when it’s time to buy groceries.

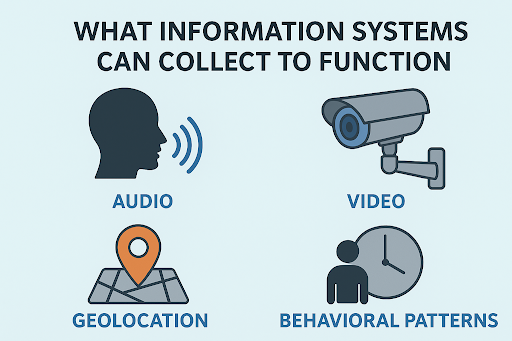

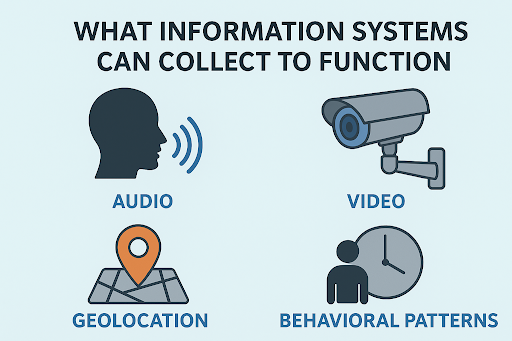

To enable such features, systems must process vast amounts of information, including:

- Audio: voice assistants record and analyze commands, and sometimes even background conversations.

- Video: surveillance cameras or doorbells with recording functions stream footage to cloud servers.

- Geolocation: mobile apps and GPS sensors track the user’s whereabouts.

- Behavioral patterns: systems analyze what hours you are usually at home, when you sleep, which routes you take, how much time you spend watching TV.

It sounds convenient and not particularly dangerous, but the biggest challenge is that much of this data collection happens without the user even noticing. Consent to “data processing” is usually given through long legal texts that almost no one reads. As a result, people often don’t even realize what exact data is being transmitted, where it’s stored, who has access to it, and how it can be used — from advertising to potential surveillance.

The paradox of the smart home emerges in the balance between convenience and the sense of security. For many users, automation and personalization are a major advantage: the system “knows” what you like and offers the best solution before you even think of it. On the other hand, there’s the unsettling feeling that devices are “watching” every move and word.

Some perceive this as a new level of comfort, while others see it as a threat to independence and privacy. This subtle psychological balance defines how people relate to technology: for some, the smart home is a friend and helper; for others, it is a potential tool of control.

Thus, the line between comfort and intrusion into privacy lies not only in the realm of technology but also in trust, transparency, and informed user consent.

Privacy Risks

Any device connected to a network can become a target for cybercriminals. If attackers gain access to the home ecosystem, they can not only intercept personal information but also control physical devices — from door locks to security systems. A data breach in cloud services run by manufacturers or providers could mean that third parties learn about users’ daily routines, financial habits, or even medical conditions.

Beyond technical risks, there is a business dimension: companies that collect information often use it for targeted advertising. Algorithms build such detailed user profiles that they can predict purchases, desires, and even moods. In some cases, there is the possibility that this data will be sold to third parties, effectively stripping individuals of control over their own digital identity.

Another issue is how deeply AI can and should “know” a person. When the system begins to understand your emotional state, what motivates you, what you fear or avoid, it shifts from being a simple tool to a potential mechanism of influence. This creates a risk of manipulation — ranging from pushing certain purchases to shaping specific behavior patterns.

Solutions and Balance

Addressing the problem of “comfort versus privacy” requires not only technical but also conceptual approaches. The key and first step here is the principle of privacy by design — when security and the protection of personal information are embedded into the system architecture from the very design stage. This means that companies must plan mechanisms for anonymization, encryption, and access restrictions not as “extra features” but as fundamental components.

Another important direction is minimizing data collection: devices should gather only the information that is truly necessary for their operation. One practical solution here is edge computing — where data is processed directly on the device or a local server rather than being sent to the cloud. This significantly reduces the risk of leaks and gives users more confidence in the protection of their privacy.

However, technical solutions are not sufficient without transparency. Companies must establish clear policies on what data they collect, how long they store it, and for what purposes it is used. Regulatory frameworks such as GDPR in Europe or CCPA in the United States play an important role by setting strict requirements for the processing of personal information and holding businesses accountable.

Finally, a crucial element of balance is user control. Individuals should be able to determine for themselves which data remains private and which can be shared. Access settings, clear permissions, and user-friendly privacy management interfaces make the user not a passive observer but an active participant in the process.

Scandals and Cases of Privacy Violations

1. Amazon Alexa: the FTC and DOJ accused Amazon of violating the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) because the company stored children’s voice recordings and geolocation data for years, even after parents requested their deletion. There were also lawsuits claiming that Alexa could record private conversations without proper consent or an active command, and that Amazon falsely promised users they had full control over which recordings were stored and deleted.

2. Google Nest: the Nest Secure camera contained a built-in microphone that users were not initially informed about. Google admitted this was a mistake, but the case highlights how a lack of transparency can undermine trust.

3. Eufy: the company faced lawsuits and regulatory pressure because some of its home cameras, doorbell cameras, and smart locks did not encrypt video streams during transmission or allowed access to video without authentication. Notably, the New York Attorney General fined Eufy’s distributors for failing to guarantee the security of private home camera footage.

Conclusion

AI and the smart home are no longer science fiction — they are becoming part of everyday life, transforming the way people interact with their surroundings and creating a new level of convenience. Yet along with this come serious challenges: from the risks of personal data leaks to the silent transformation of daily life into a field for total data collection.

The key task is to find a balance between innovation and the human right to privacy. Principles of transparency, data protection, and the ability for users to control their own information must become the foundation for the development of this field.

In the end, the choice will always remain with the individual: how much privacy one is willing to trade for comfort, speed, and personalization. And it is this choice that will determine what the new culture of interaction with technology will look like in the future.