✆ + 1-646-235-9076 ⏱ Mon - Fri: 24h/day

How Not to Write Code You’ll Hate Later

Every developer has found themselves, at least once in their career, in a situation where they start working on a project — or return to it after some time — open the code, and don’t recognize it. «Did I really write this? What is this? Who did this? How on earth is this my code?» — terrifying questions that send chills down your spine.

When you start recalling the details, it kind of makes sense: rushing toward a deadline, trying to «just make it work», or simply not having the time to think through the architecture. But months later, that same code turns into a trap — bulky, confusing, and hard to debug.

What we later call «terrible code» is rarely the result of a lack of technical skill. It’s easy to blame juniors for all the problems, but even experienced developers face this. Most often, bad code is the outcome of situations where the priority becomes instant results rather than quality or long-term solutions. We sacrifice structure, meaningful naming, tests, or documentation, convincing ourselves that «we’ll fix it later». We wait for that mythical moment when there are no tasks left — but that time never really comes.

The problem of «code you’ll hate later» isn’t just about style or formatting. It’s about habits, discipline, and inner calm — even under tight deadlines — and about thinking long-term. Writing good code doesn’t mean striving for perfection; it means creating something that remains clear, predictable, and painless to maintain even six months later. As they say: KISS.

Understand the Real Enemy: Shortcuts and Pressure

If we’re being honest, most «bad code» is born out of haste. We’ve all been in that situation — the deadline is burning, the manager keeps reminding us about the release, and instead of a well-thought-out solution, your hand automatically reaches for the quickest «quick fix». The thought «I’ll rewrite it later, the main thing is that it works now» soothes professional anxiety.

Temporary solutions start piling up, turning into technical debt — that invisible weight which, with every release, slows down development, increases the risk of bugs, and makes the system fragile.

There’s a difference between a «quick fix» and a «temporary patch that lives forever»:

- Quick fix — a conscious short-term solution with a clear plan for replacement or improvement. You know it’s fine for now, but there’s already a ticket for fixing and developing a better approach.

- Temporary patch — chaotic hole-patching without any strategy, which stays in production for years, eventually creating a «snowball effect».

A typical example might be a situation where you need to quickly add a new field — say, the account type — to the user management module. An unexpected task that takes 1–2 hours.

But such a change, especially at the end of a sprint, adds extra load that might already be high. And instead of updating the user model and services according to SOLID principles, the developer simply adds a String userType and a few conditions like if (userType.equals(“admin”)) …. It works, tests pass, everyone’s happy. All sprint tasks are completed.

However, after a few more sprints, as new user types appear and the logic expands, the code turns into a web of conditions that’s scary to touch. A new refactoring task appears — and you’re lucky if the estimation for it is adequate, not the same 2 hours in which you’re expected to do two or even three times more work.

Thus, one hasty compromise in class structure can ruin architectural clarity and turn future updates into complete chaos.

The real enemy isn’t the deadline or our past selves — it’s the habit of letting speed outrun quality. And realizing that this isn’t okay is the first step toward building the habit of always writing code the right way.

Principle #1: Write Code for People, Not for Machines

When we write code, it’s easy to forget that the computer doesn’t care at all what it looks like.

It doesn’t matter to it whether there are indents, comments, or meaningful names — it will execute anything that’s syntactically correct.

But humans are a different story. Code is read dozens of times more often than it’s written. That’s why clean, readable code is a huge investment in maintainability. Clear names for variables, methods, and classes immediately convey the author’s intent without the need for extra comments. The code should speak for itself.

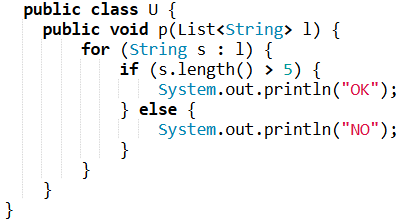

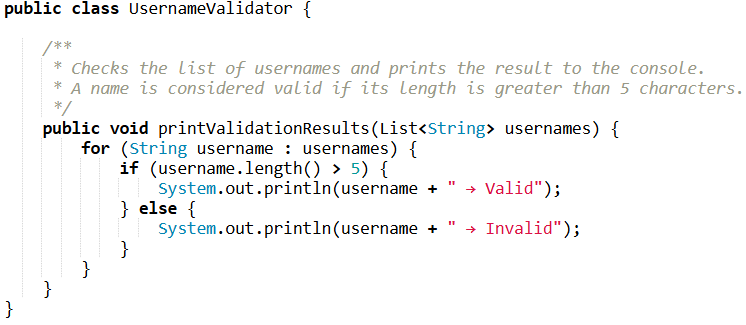

Example of bad code:

Everything works fine here. But what is this? Who is «U»? What does «p()» mean? What’s that list «l»? A week later, even the author won’t remember what they meant.

(Author’s note: if you’re reading this and everything looks fine to you — and you even recognize your own code — it’s time for a serious talk with yourself.)

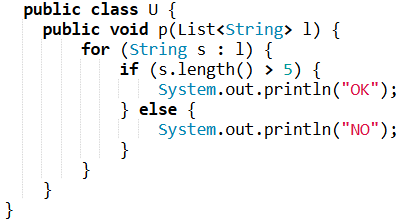

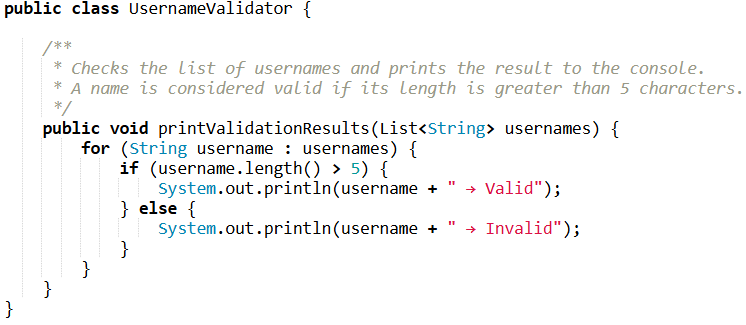

Example of good, readable code:

Here it’s immediately clear:

- the class handles user name validation;

- the method checks a list and outputs the result;

- variables are named according to their purpose;

- there’s a short but meaningful comment.

Well-written code doesn’t need to be deciphered. It reads like text, not like a riddle. And when you or your colleague return to this method in six months, you won’t have to waste time guessing what «p()» or «l» means. It’s a win-win situation — your teammate is happy, your karma is a little cleaner, and there are fewer curses sent your way.

Principle #2: Small, Focused Functions

One of the most common mistakes developers make — and one that often causes problems later in a project — is huge methods. Such code is written quickly and tends to grow even faster. A method that started with just a few lines can easily turn into a 50-line monster that does everything — from validation to logging. That’s exactly why the Single Responsibility Principle exists: it means a method should have one clear purpose. If it does more — that’s a signal for refactoring. Small, focused functions are easier to read, test, and reuse.

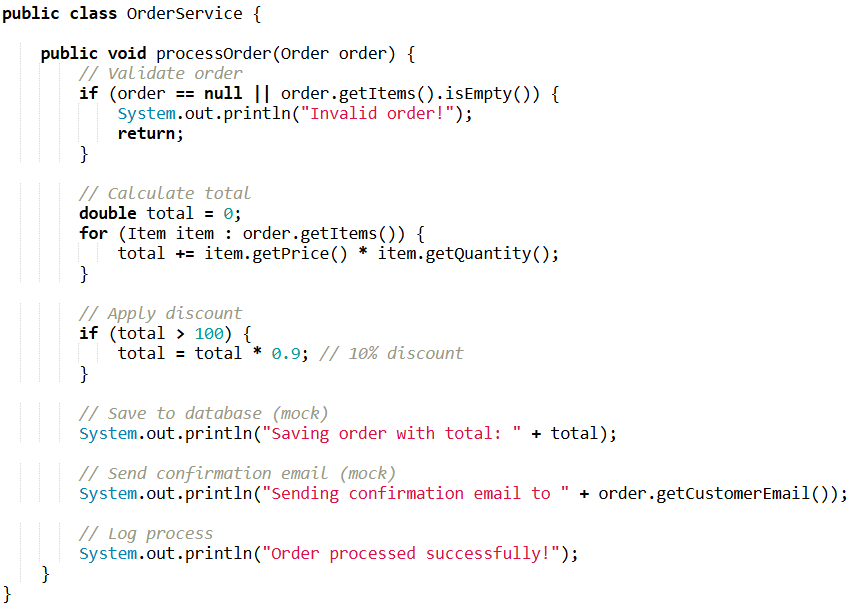

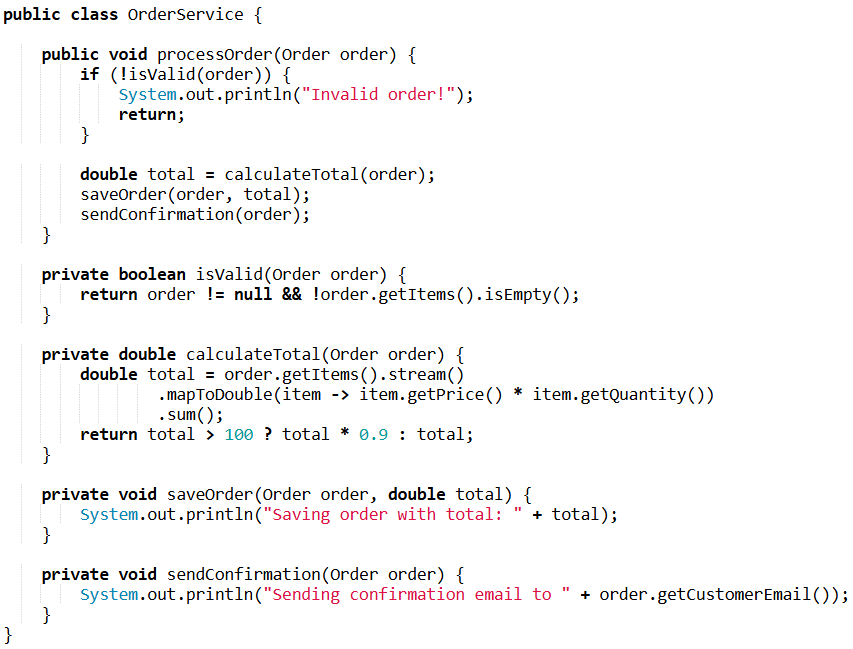

Bad Example: one giant method

This method does everything at once — validation, calculation, discount, saving, email sending, and logging. Changing or testing just one part of it is nearly impossible without touching the rest.

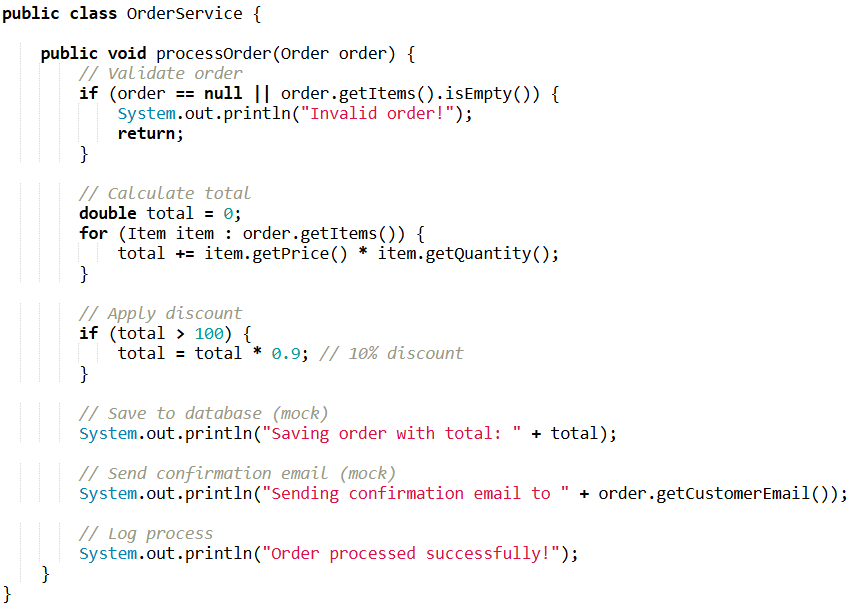

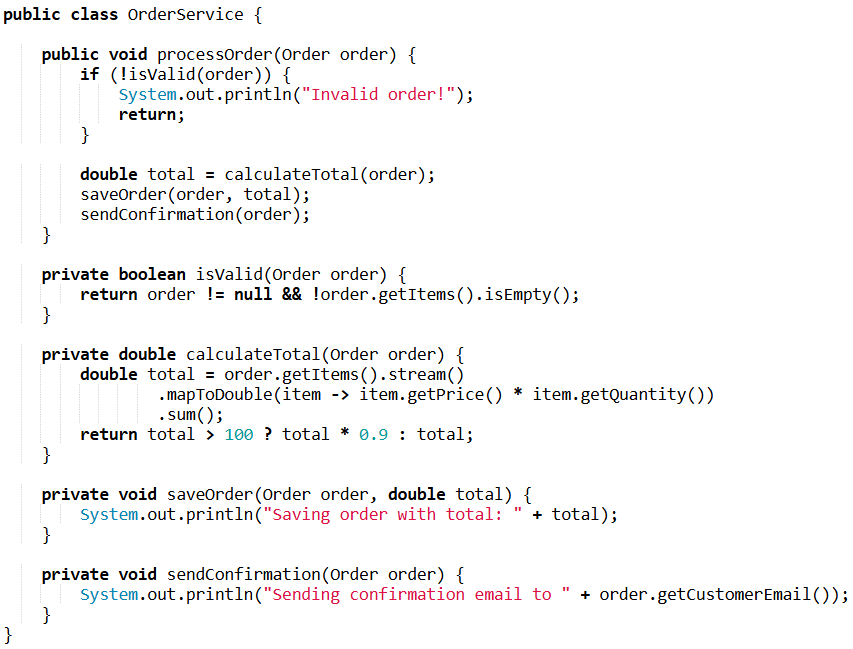

Good Example: refactored into three smaller methods

This structure makes the code clear, flexible, and easy to test. Even without comments, the logic remains obvious. You can modify the discount logic without affecting anything else, or test only calculateTotal() without dealing with other dependencies.

Principle #3: Don’t Reinvent the Wheel (But Understand It)

One of the less obvious traps for developers is neglecting existing solutions. This happens for different reasons — and not always because those solutions don’t fit the project. Sometimes it’s just laziness: not wanting to read documentation or figure out what someone else has already implemented. This leads not only to strange, redundant functions appearing in the codebase but also to repeating work that’s already been done — sometimes several times over. For example, imagine you need to use a cache somewhere in the program. You might think: why bother searching online, picking a library, and reading its documentation just for one small use case? «I’ll just write my own». And that’s not always a terrible decision — it can work fine for a small system. But you have to understand all the potential risks. Once the system grows and caching becomes more widely used, it can quickly turn into a source of problems: inefficient cache clearing, memory leaks, multithreading bugs, and no TTL (time-to-live) support.

There are mature libraries that already solve these issues — for example, Caffeine. It’s optimized, well-tested, and supported by the community. However, it’s equally important to understand how the tools you use actually work. Because if one day the cache starts behaving strangely, and you don’t have a basic understanding of caching algorithms (LRU, LFU, expiration), you won’t be able to debug it properly.

Principle #4: Think About Future You

When the stage of active development is in full swing, a developer is usually immersed in the entire context of what’s happening — everything is fresh in their mind. But six months later, that context disappears, and even the smartest algorithm can look like either magic or nonsense if it exists without any guidance.

That’s why, when writing code, your goal should be to help your future self understand what you meant when you wrote it.

Here’s what can help:

- Documentation: a short Javadoc before a method can save a lot of time. To keep things clean, there’s no need to rewrite the logic in words — just describe the method’s main purpose and clarify any non-obvious details if they exist.

- Testing: think of it as insurance against problems. Unit tests are like that annoying but reliable friend — sometimes tedious, but always making sure you can move safely through the project.

- Logging: like a patient’s vital signs during surgery. If there’s nothing — that’s bad news. If there is — it helps not only confirm that things are running correctly but also reveal hidden problems.

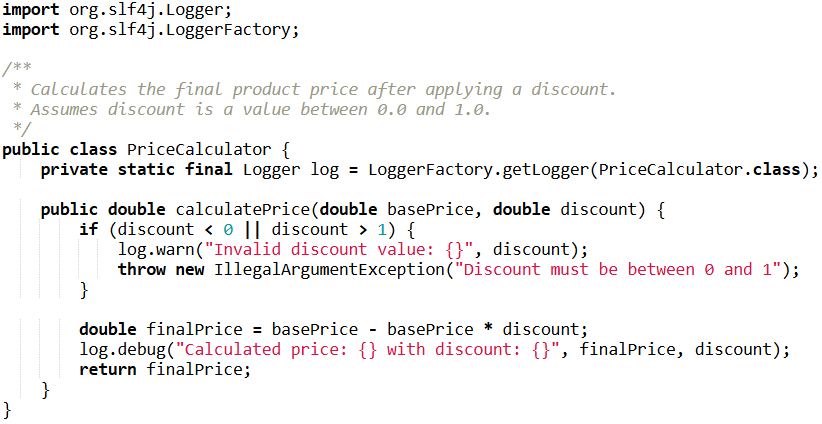

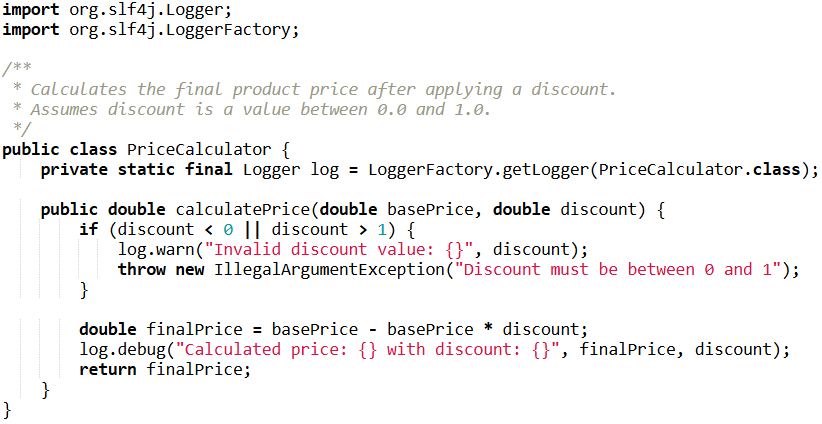

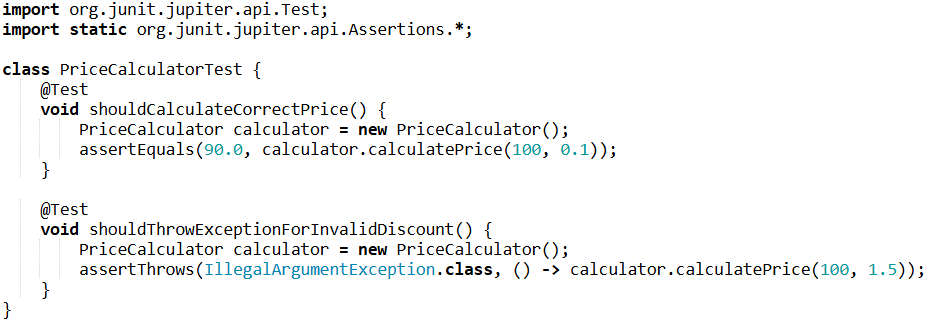

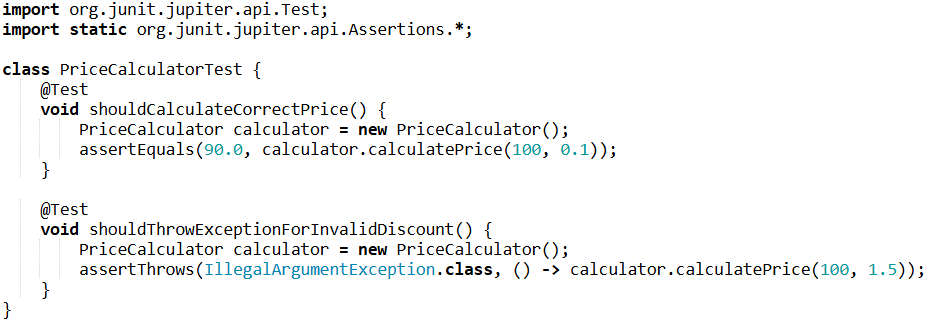

A good example — documented, tested, logged:

And a separate unit test:

It’s important to understand that there isn’t always time for tests and documentation (logs, however, are a must-have everywhere — though they too should be used wisely), especially in small projects. But if you skip them, you should be aware of the risks — and always plan to add them later.

Principle #5: Refactoring as a Habit, Not a Project

You can think of refactoring as a separate, big phase of a project — something you’ll do later, «when there’s time». That approach has its place. But it’s far more effective to make refactoring a part of everyday development, not a rare, one-time event.

Small, regular improvements — renaming variables, breaking large methods into smaller ones, removing duplication — bring much more value than massive overhauls. This approach minimizes risks and continuously maintains the project’s quality. Refactoring isn’t a heroic cleanup after chaos — it’s the habit of keeping things tidy every day.

Conclusion

In the end, «good code» isn’t about perfection — it’s about predictability, simplicity, and care. It’s about opening a file six months later and thinking not «What was I even doing?» but rather: «Oh, I actually did a pretty good job here».

Good code is an investment in your own peace of mind — in faster releases, fewer bugs, and healthier nerves. It doesn’t come from perfectionism — it comes from discipline, attention to detail, and the desire to leave behind something clear and understandable. «You don’t write perfect code — you write code that’s easy to improve».